Scratching an itch: Dandruff could be definitive

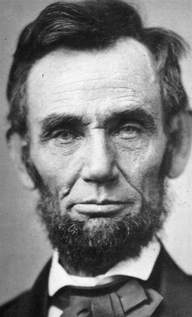

If Abraham Lincoln were alive, would he need Head and Shoulders?

The answer could settle whether a hat on display at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum actually belonged to Abe.

The hat is believed to have been Lincoln’s lid, but there is no proof. As first reported by the Chicago Sun-Times, an affidavit from a prior owner doesn’t hold up. According to the affidavit, Lincoln was in Washington, D.C., when he gave the hat to a political supporter from Illinois. But the purported recipient, it turns out, never traveled to Washington while Lincoln was president. Museum officials have explained the discrepancy by suggesting that Lincoln gave his hat away before becoming president, but there is no proof of that, either.

The only certain things are that the hat was made in Springfield and would have fit Lincoln. Nonetheless, the museum display contains no hint that the hat has anything but an ironclad provenance, and museum officials have insisted that the hat is genuine.

Dandruff could settle the question. Dandruff is loaded with DNA – indeed, experts say there is more DNA in dandruff than in bones. Just ask Andrew Pearson, who was convicted in 2004 of an 11-year-old bank robbery in England after investigators matched flakes of dandruff found in a stocking worn as a mask with DNA from Pearson.

James Cornelius, curator for the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum, said the question of conducting DNA tests on the hat comes up regularly. He said the museum has checked the hat for hair and found none, but he wasn’t aware that dandruff contains DNA. Cornelius noted that there has not been a DNA profile developed for Lincoln, so there would be nothing to compare a sample with even if DNA were found in the hat. He added that the museum is concerned that testing could damage the hat.

But DNA experts say the hat could be tested without damaging the artifact, and comparison testing could be done by comparing DNA in the hat with DNA gathered from objects that came in contact with deceased descendants of Lincoln.

But DNA experts say the hat could be tested without damaging the artifact, and comparison testing could be done by comparing DNA in the hat with DNA gathered from objects that came in contact with deceased descendants of Lincoln.

Even if Abe was dandruff free, the hat could contain DNA from skin cells on Lincoln’s – or whoever’s – forehead that sloughed off and worked their way into fabric inside the hat, according to several DNA experts who agreed that testing the hat for DNA could definitively establish whether the hat was worn by the Great Emancipator.

“Absolutely,” said Monte Miller, a former forensic scientist with the Texas Department of Public Safety crime laboratory who now works for a private lab in California and testifies as an expert witness in court cases. “If it’s kept dry and in a cool, and hopefully dark, environment, it’s (DNA is) good for hundreds of years without any problem.”

Miller and other experts agreed that storage conditions are critical. Moisture and light cause DNA to deteriorate. If the hat had been worn by others after Lincoln owned it, recovering Abe’s DNA could also be problematic, but not impossible.

“The more it’s handled, the less likely that you’re going to be able to get a good DNA profile,” Miller said.

If Lincoln had worn the hat more than any other person, his DNA would have soaked into the brim and could be present in a higher concentration than any other DNA, Miller said. If Lincoln had tipped his hat with a cut on his finger that left a trace of blood, the chances of success would go up, according to Richard Eikelenboom, a Dutch DNA expert who testified for the defense in the murder trial of Casey Anthony.

Cutting a sample from the hat would be the best way to test, according to Miller and Eikelenboom. Miller said the sample could be as small as 1/32 of an inch square, although a sample of one-eighth of an inch square would be ideal. Alternatively, samples could be obtained with tape, which would not damage the hat, or by swabbing the hat. The experts said testing would likely cost a few hundred dollars.

“We would not damage the hat at all,” says Brian Meehan, a professor of forensic biology at Ohio Northern University who testifies as an expert witness and recommends swabbing the hat.

Meehan said his lab would test the hat for free. Alternatively, the museum could pay to have the hat tested in confidence and would be under no obligation to release test results, Eikelenboom said.

“Every serious forensic lab has confidentiality,” Eikelenboom said. “If you’re not happy with the result, you don’t have to tell anyone.”

While there is no known DNA profile of Lincoln and no living direct descendants, a comparison sample could be obtained from objects touched by Robert Todd Lincoln Beckwith, a great-grandson of Lincoln who died in 1985. A licked postage stamp would do, Eikelenboom said. A comparison sample could also be obtained by swabbing bloodstained artifacts preserved after Lincoln’s assassination, Meehan said.

If no DNA was recovered from the hat, or if DNA found on the hat didn’t match Lincoln’s DNA, that doesn’t prove the hat didn’t belong to him, Eikelenboom, Miller and Meehan agreed. The experts said they don’t see a downside to testing the hat for DNA, but the upside could be tremendous

“The only thing to do is try it,” Meehan said.

Contact Bruce Rushton at [email protected].

Read Bruce Rushton's article on the Illinois Times website.

| chevron_left | Reducing laboratory fume hood energy consumption, even at 100fpm face velocity! | Articles | Join us at Pittcon 2013 | chevron_right |